The pioneer period in Kansas was drawing to a close when the people adopted statewide prohibition. My husband was among the pioneers in the movement. During the war he had joined a temperance society, the chief object of which was to educate the soldiers regarding the evils of drink. Christian learned, however, that drunkards often were unable to give up liquor even when they wished, because it was always at hand to tempt them.

From that fact he early became an advocate of antisaloon laws. When we migrated to Kansas, there were saloons at Sabetha, which was our nearest trading center before the railroad came to Fairview. A few years after our arrival Christian launched a campaign against the Sabetha saloons. By a series of letters to the Sabetha newspapers he roused public opinion to the point that a group of merchants petitioned the town council to abolish saloons. The saloon keepers tried to discredit the project by pointing out that the dry leader was a farmer living five miles from the town limits, who by his non-residence had no voice in municipal affairs. Christian answered with letters declaring that since Sabetha owed its life to the trade of the farmers, the farmers, in turn, had a right to discuss the town's policies. The next move of the wets was an attempt to prevent the newspapers from printing Christian's letters. But one editor, who was himself an imbiber, encouraged Christian to continue his onslaughts on rum.

Eventually, Sabetha voted dry; and Christian won recognition, which put him at the head of future dry campaigns in our vicinity. The saloon faction determined, therefore, to discredit his leadership by an endeavor to force him to vote according to its orders by threatening to ruin his contracting business, which he had kept up in a small way since coming to the farm. One day the leader of the Fairview rum faction approached him with instructions to vote for a certain wet candidate for county commissioner. This office was important because the commissioners had the authority to issue or deny dramshop licenses in the county outside of incorporated places. Now it happened that the wet candidate was am acquaintance of ours, and out of friendship Christian had intended voting for him, but he never was a man to take orders and said so.

"All right," threatened the captain of the rum faction. "Then we'll ruin you in business and otherwise."

This brazen threat roused Christian's resentment so much that he promptly decided to vote for the dry candidate. In those days the secret ballot was unheard of, and, of course, everybody soon knew how my husband voted. Immediately the wets carried their threat into execution. They adopted a whispering campaign against him. They called on all new settlers, who, of course, were the only people with houses to build, telling such lies about my husband's ability as a carpenter that no one would give him a contract to drive as much as a shingle nail. In reality that was a good thing for us. Christian was so conscientious that he seldom made more than wages on his contracts, and often less than wages. By losing his contracting business, he was able to give more time to farming, and that was to our benefit. On the other hand, the attempted coercion turned Christian into a fiercer enemy of saloons than ever.

The election which brought in state-wide prohibition came in 1880 and was preceded by a thoroughly organized and hotly contested campaign. The chief strength for prohibition in our part of the county centered in the membership of Fairview church, while opposition to the amendment was strongest among the class who could "take a drink or leave it alone." Many of the wets were church members, a few being adherents of our own church. A third class, which had to be reckoned with in the campaign, were the drunkards; and in that class were a good many supporters of prohibition. I knew several habitual drinkers who voted against the saloon. One of them remarked in my hearing:

"I like whisky too well, but I am better off if I don't drink it, so I will vote to put it where I can't get it."

Mass meetings were held at the neighboring towns and at the Fairview church. Everybody was keenly interested on one side or another. People felt so intensely on the subject that old friends quarreled and there was disruption in the community. Those of us who favored prohibition did so because we wished to rear our children beyond the influences of the saloon, and because we wished to remove the temptation from the drunkards who could not resist it. On the other side, the saloon supporters argued that prohibition would interfere with personal liberty and that it would destroy the market for barley.

Chief of the dry campaigners was John P. St. John, our governor. Many speakers also came from outside the state; among them was Col. George A. Bayne, "the silver-tongued orator," from Louisville, Kentucky, who stumped Kansas for prohibition. Another was Mrs. M. E. DeGreer Call, of Chicago, editor of The Crusader. She addressed a crowded house in the Fairview church, at which, after discussing the curse of drink, she turned to the women and said:

"You women cannot vote, but you have tongues. As you ride along the highway, do you hesitate to warn your husbands if you see that they are driving into mudholes? You do not. Then why should you hesitate to advise your husbands at the election?"

Click here for a larger image

Click here for a larger image

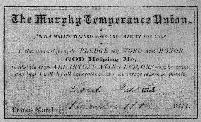

Another feature which brought out crowds was the pledge signing. At the close of each meeting both young and old were urged to come to the front of the church and sign the teetotaler's pledge. Such an act entitled the signer to wear the temperance insignia, a blue ribbon. Of course, when a great speaker like Governor St. John, Colonel Bayne, or Mrs. Call was on the platform, the number of pledge signers was increased, which in turn helped to swell the attendance of wets as well as drys; for those who cared nothing for the cause regarded the pledge signing as entertainment.

Click here for a larger image

Click here for a larger image

When election day arrived, the women went to the polls as Mrs. Call advised. Some who felt that they were unfitted for electioneering went to the church to pray. As everyone knows, the drys won the election. While prohibition reduced drinking, it did not end it. This was due party to the bootleggers and partly to the brewers and distillers of other states who had no respect for our state's laws. Whiskey could still be sold in cellars and other hidden places. The law failed to save the confirmed drunkards, but it did drive the saloon from the main streets.

Nor did we stop with mere enactment of the law to promote sobriety. Provision was made in the public school curriculum for teaching the evil effects of alcohol. School children were supplied with physiologies illustrated with views of the interior of the stomach of a temperate man, of a moderate drinker, and of a hard drinker. By such methods children were taught that alcohol was bad for the body. As a result of the teaching the bootlegger became a pariah in the community. During the fifty-four years of prohibition in Kansas, babies have been born and grown up to be grandparents, away from the sight and smell of the open saloon. Strive as we would, we never could keep liquor away from all the old soaks, but they are dying off and are being replaced by a newer generation which is so well satisfied with prohibition that they approved it in November, 1934, by an overwhelming majority. My husband lived to see the day when those who had boycotted him in the eighties came forward to tell him they had been wrong and he had been right.